Regarded as one of the greatest comedians of all time, the award-winning actor Robin Williams passed away in August 2014. Williams willed most of his estate to his three children in his estate plan but included an interesting clause. This clause prohibits the use of his image or any likeness of his image for 25 years after his death before passing on image rights to his charity organisation. This unique situation raises an important question:

“Who owns the art after the artist is gone?”

With the advent of technological advancements, humanity can still appreciate the artistic expressions of artists posthumously. By Californian law, Robin Williams’ choices are protected for up to 70 years. This legal reform and unusual request came long before the development of AI and points to one clear fact: artifacts and artistic relics hold significant economic and social value.

In the era of cutting-edge visual effects and the ability to replicate any likeness, it is interesting to see these operations affected by legal constraints. However, such a precedent does not exist in most Western countries – or Zambia. If it did, such a law would have set a precedent to argue for many ancestral artifacts. The law is alive, changing as humanity changes, and what is right in one generation could become obsolete in another. In the context of repatriation, the British Museum acknowledges that the Benin Bronzes were taken during a period of “widespread destruction and pillage” by soldiers. As such, an object acquired under historical contexts may not align with contemporary views on justice.

Legal reform has yet to catch up to technological advancement, and it is up to individuals to protect and preserve what matters most to them. We live in a world of posthumous albums and brand campaigns. Still, Williams’ actions make a powerful statement about self-propriety, who owns art, legal reform on intellectual property, and how a digital revolution is shaping the arts.

National treasures like the Egyptian hieroglyphs and the pyramids are immovable, but the Benin Bronzes of Nigeria, the Bangwa Queen of Cameroon, the Nefertiti Bust of Egypt, the Zimbabwe Bird, and the Broken Hill Man of Zambia are among many priceless precolonial artifacts that were removed from their place of origin.

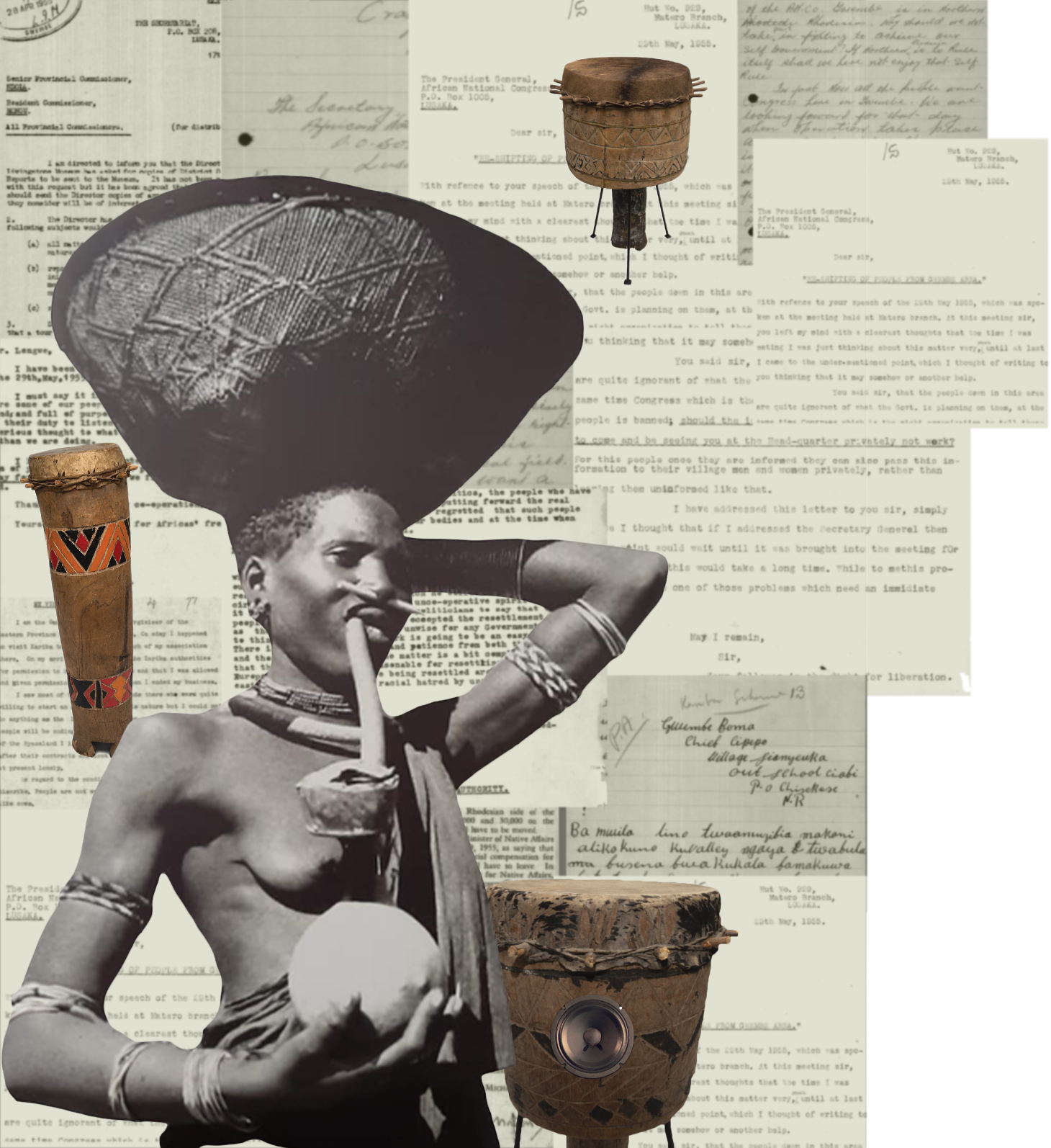

“Zambia was first subject to imperial conquest in 1888 when the British South Africa Company secured mineral rights there. It subsequently became a British protectorate in 1899. Throughout our tumultuous colonial history, we have been a casualty in the displacement of artifacts, distortion of culture, and the dilution of records… Zambia’s identity has become muddied and fragmented… However, the rise of the digital era has helped to combat the lack of access to our histories and the instability and fracture in identity (especially within the younger generations), as digital frameworks foster African people regaining the keys to their cultural background. There is an urge to reclaim artifacts and champion communities within these histories who were disenfranchised and disregarded due to one-tracked systems of knowledge production.” – Source: European Pro

Our History, Our Story

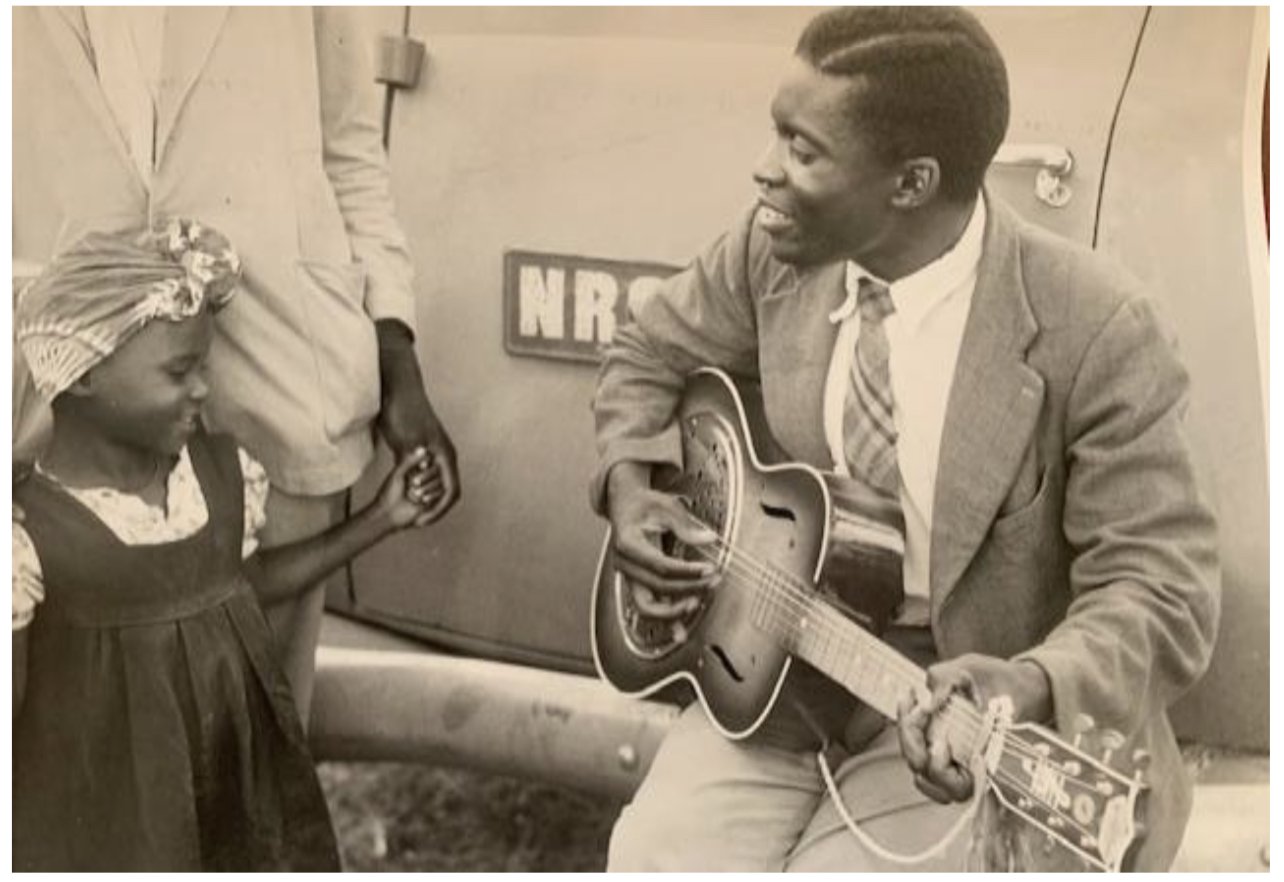

Zambia is a young country with a median age of 17. As digital penetration increases, this growing population is gaining early access to the internet, resulting in an information boom. Digital frameworks have created a unity grounded in internet accessibility and social networks, and today’s generation is more connected than ever before. Despite this interconnectedness, knowledge gaps persist, limiting the engagement and participation of indigenous African communities.

Those favouring artifact repatriation argue that objects created within a particular culture belong to that culture. Many cultural objects have sacred meanings prescribed at their place of origin that are lost and distorted when taken out of context. Culturally, numerous cultural gourds, beads, and instruments are meant for something other than public viewing or display. There are objects that should be together but are separated. For example, the people of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) have a stone moai statue standing in a foreign museum containing the spirit of an ancestor who can no longer protect descendants on the island. Returning these objects also helps community members pass on their culture to the next generation. There are many examples of new generations that will not know the practices and traditions of their forefathers simply because the objects critical to the practices are now out of reach.

The Role of Digital Restoration

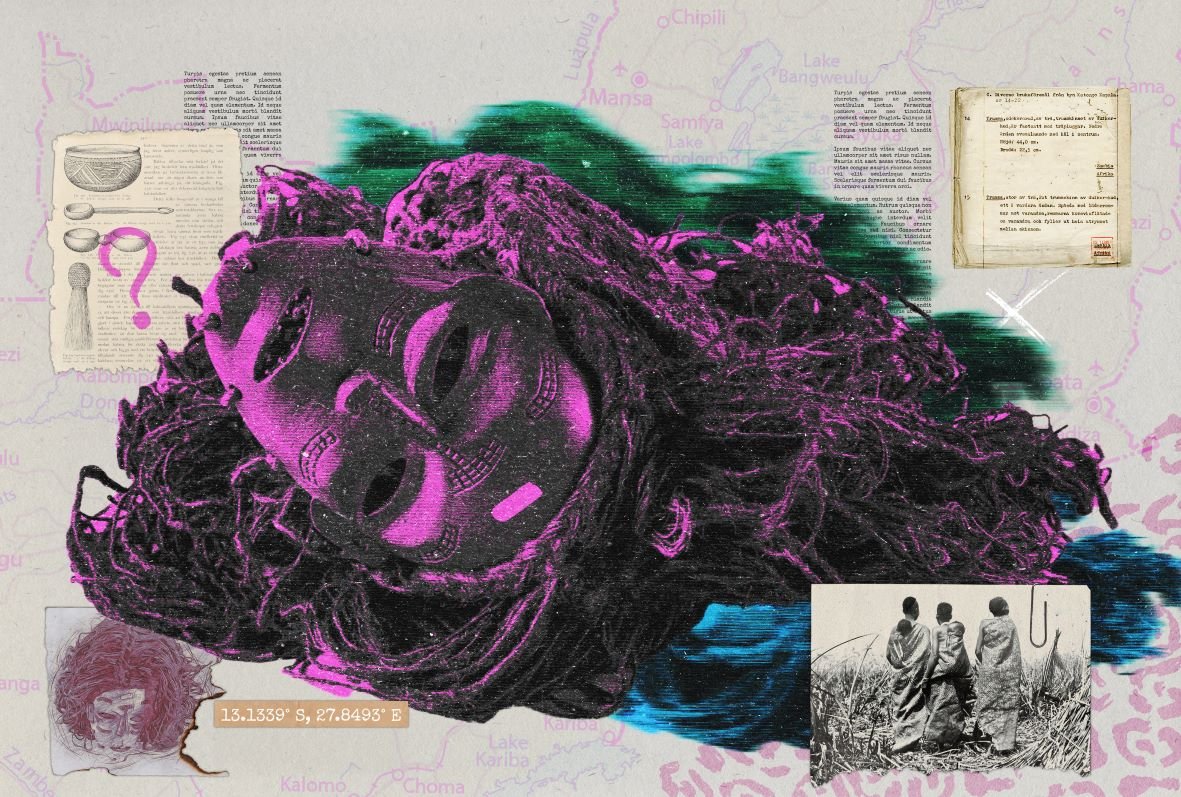

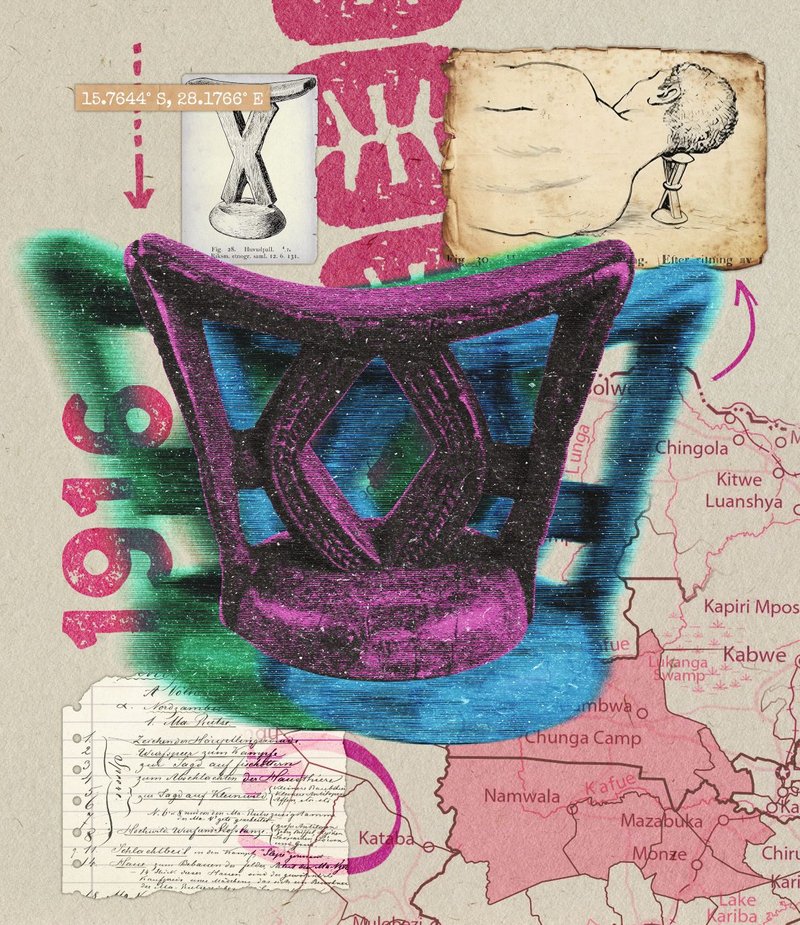

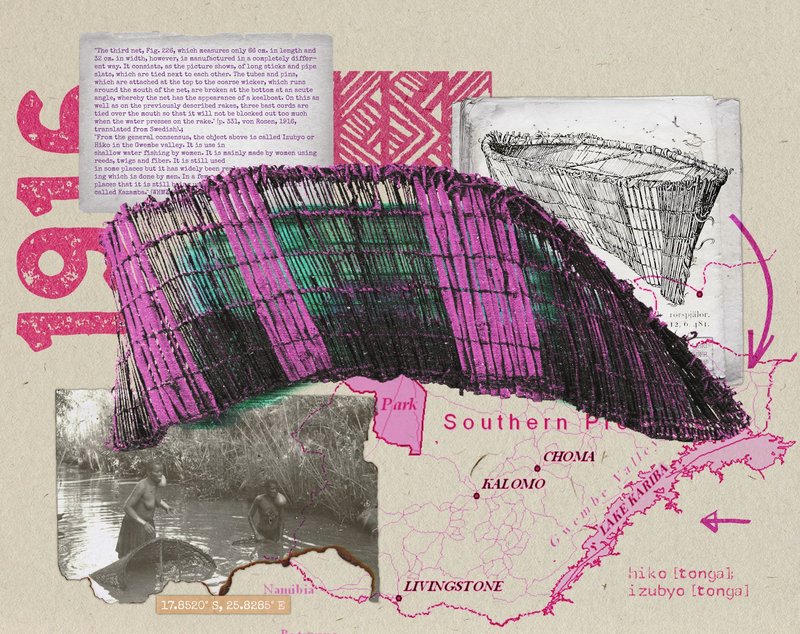

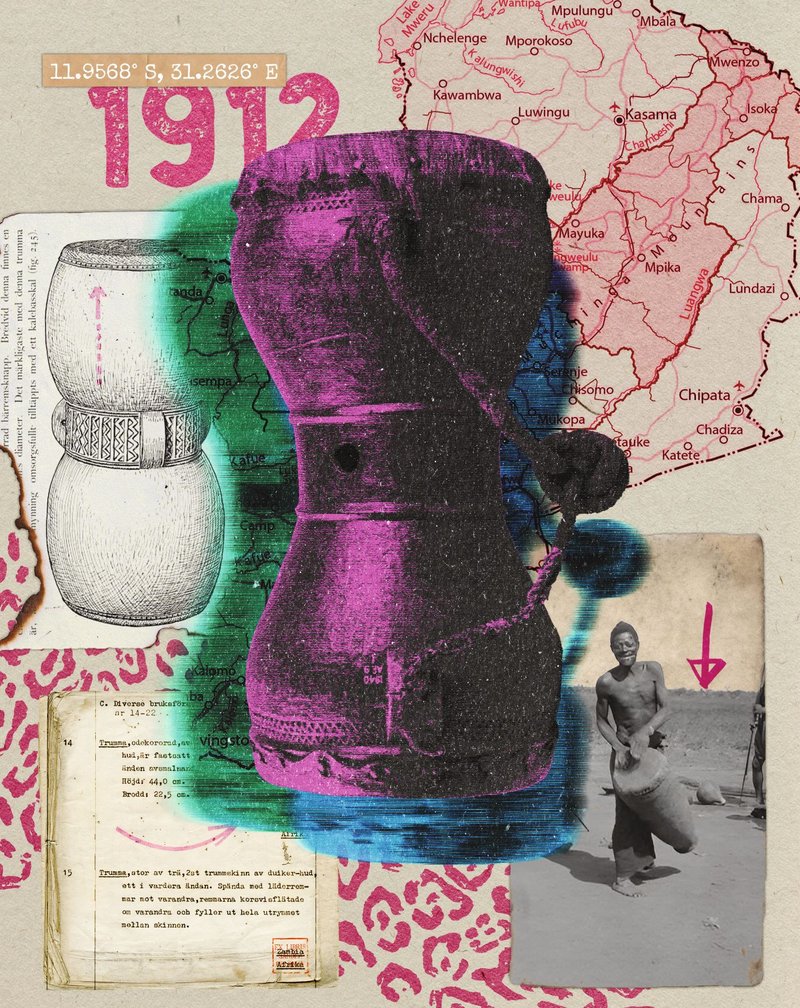

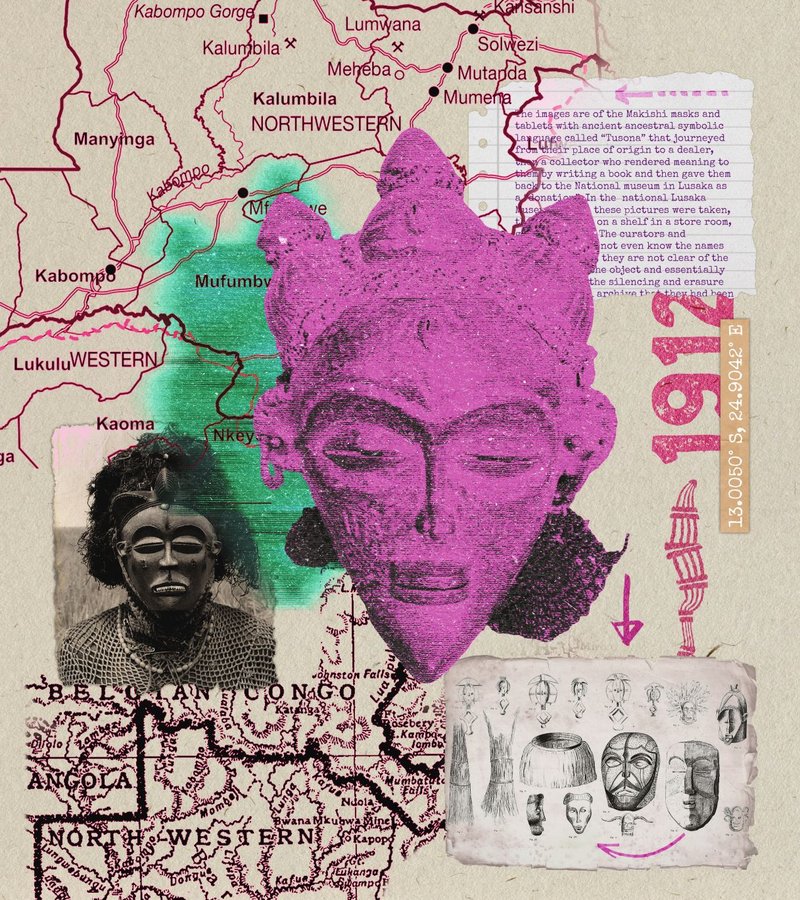

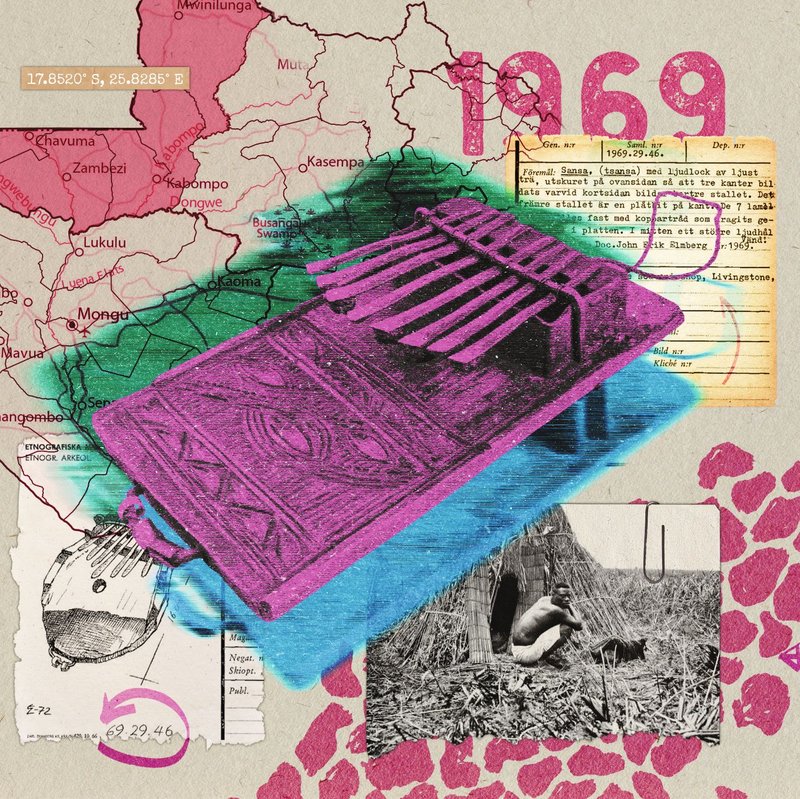

In Zambia, The Women’s History Museum has a mission to cultivate cultural heritage and preservation. They have conceived the Shared Histories project through a partnership with the National Museums of World Culture in Sweden. This collaborative digital platform is centred around cultural object repatriation through digital means. Shared Histories works to address the gap in cultural knowledge by providing and increasing accessibility to Zambian cultural objects which have, over centuries, found their way outside of their communities of origin. Through the attentive restorative digital curation of the sacred ceremonial masks, intricately woven baskets, and indigenous objects, there is an opportunity to show the experiences and contributions of the owners of the tradition and heritage.

These are part of a narrative that may have been erased from Zambia’s mainstream socio-economic and cultural history due to the country’s colonial legacy and post-colonial tensions. The Swedish Ethnographic Museum and The Women’s History Museum of Zambia developed a proposal to address this matter. The proposal created a collaborative and interactive digital interface for sharing historical collections and women’s histories between Sweden and Zambia, which was approved for funding by the Swedish Institute.

Through extensive provenance research programmes, the project facilitates the healing of metadata in Zambian histories and objects that remain in the SMWC’s physical collections. The impetus behind these programmes is to re-centre the voices of the original makers of the objects and the original owners of the histories in the narratives attached to the collections they rest in. A planned extension of the Shared Histories project is facilitating technology literacy workshops in remote areas of the country with high concentrations of relevant living histories.

Returning these objects cannot fully rectify colonialism’s impacts, but it would allow for new ownership, storytelling, and an opportunity for African nations to reclaim their identity narratives.

Does Physical Ownership Matter?

Simply acknowledging that the artifacts belong to Africa is not enough. Many of Africa’s cultural treasures are housed in foreign museums, where they hold significant aesthetic and monetary value and attract many tourists. However, their stories are often retold and reframed, losing the original context and purpose. The process of repatriation is rarely straightforward. Aside from human interest, some laws stand in the way of African nations reclaiming their objects from Western nations and museums.

The National Museums Board is currently working on bringing the remains of The Broken Hill Man back from the Natural History Museum of London. Object repatriation is a national project that citizens, corporations, and international governments must support.

The remains of The Broken Hill Man tell us about the evolution of human beings in Zambia. To the National Museums Board,The Broken Hill Man is more than cultural heritage; such an artifact would act as a revenue magnet. Reclaiming The Broken Hill Man could elevate the richness of the stories we tell and direct tourists to our museums.

Artifacts offer more than intellectual stimulation; for Zambians, they are a portal of understanding that brings identity, creativity, healing, and harnessing of Indigenous knowledge to light. For generations, artistic objects and artifacts have been housed in foreign museums, far from their indigenous origins, due to their perceived contribution to humanity as a whole. There is an argument that African nations are unequipped to care for and preserve priceless objects that stand to benefit us all. There is the school of thought that history belongs to all humanity, and those best equipped with state-of-the-art facilities must maintain them for our benefit. Valid fears of vandalism, theft, corruption, and natural decay plague nations and museums unwilling to repatriate cultural objects. The condition of the papier-mâché replica of Broken Hill Man in Lusaka highlights the validity of these concerns. There is also the underlying fear of potential widespread legal reforms that could lead to many Western museums losing a significant portion of their collections, as some are reported to have up to 8 million African objects.

The National Museum Board is currently working with UNESCO to build the capacity to care for Zambian artifacts once repatriated and to spearhead the return of The Broken Hill Man. Through their expertise, the Board is undertaking to make the investment required to preserve Zambia’s artifacts. With support from theJapan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), they have increased the skill capacity of local teams and acquired instruments such as incubators and fumigators that will create the best environment for artefact preservation.

It is a good start. African appreciation and preservation of cultural artifacts is not yet perfect, but value can be taught and capacity built. Digital repatriationand conversations around the return of the objects acknowledge their source, spark interest, and allow for the restoration of dignity. If art is indeed for all of humanity to enjoy, then it must be in the context in which the artist created it. Ancestors may not be able to conventionally permit the exhibition of the objects that pointed to how they lived their lives, but setting the record straight is a form of honour.

A call for individual responsibility by African communities is necessary. Before taking the giant leap to ownership, the first step is interest, curiosity, and commitment. Only then will we discover what was taken, what is missing, and how it can be restored. Our culturally significant objects have a transformative power waiting to be uncovered and brought back home.

Illustrations by Macdonald Moyo