June 24th 1987 was a surreal day for the Chisha family. They welcomed into the world another bundle of joy. A bundle of joy that would go on to bend the lines between what was real and what was not.

As a child Caleb Chisha was, in his own words, an artistic person. All of his hobbies and pleasures involved some element of art.

“I made a lot of figures and paintings, I don’t even know where they are. Besides these common things that all kids made, like wire cars – I was the best.

Even as a career I just wanted to be an artist. And I’m the only one in my family who grew up to be what he wanted to be. I didn’t want to do something I was forced to just for the money or because my parents forced me, but I wanted something that I was really from the heart.”

In his primary school years he would sit and long for an opportunity to go to school and actually learn a subject he enjoyed. He still has fond memories of when he was told that art was a subject.

“I was so excited. I couldn’t wait to go to grade eight. All I could think of was I would get to learn art.”

Born and raised in the friendly city of Ndola, Caleb Chisha grew up in a full home and painting wasn’t always his dream.

“I grew up with my family. There were ten kids.

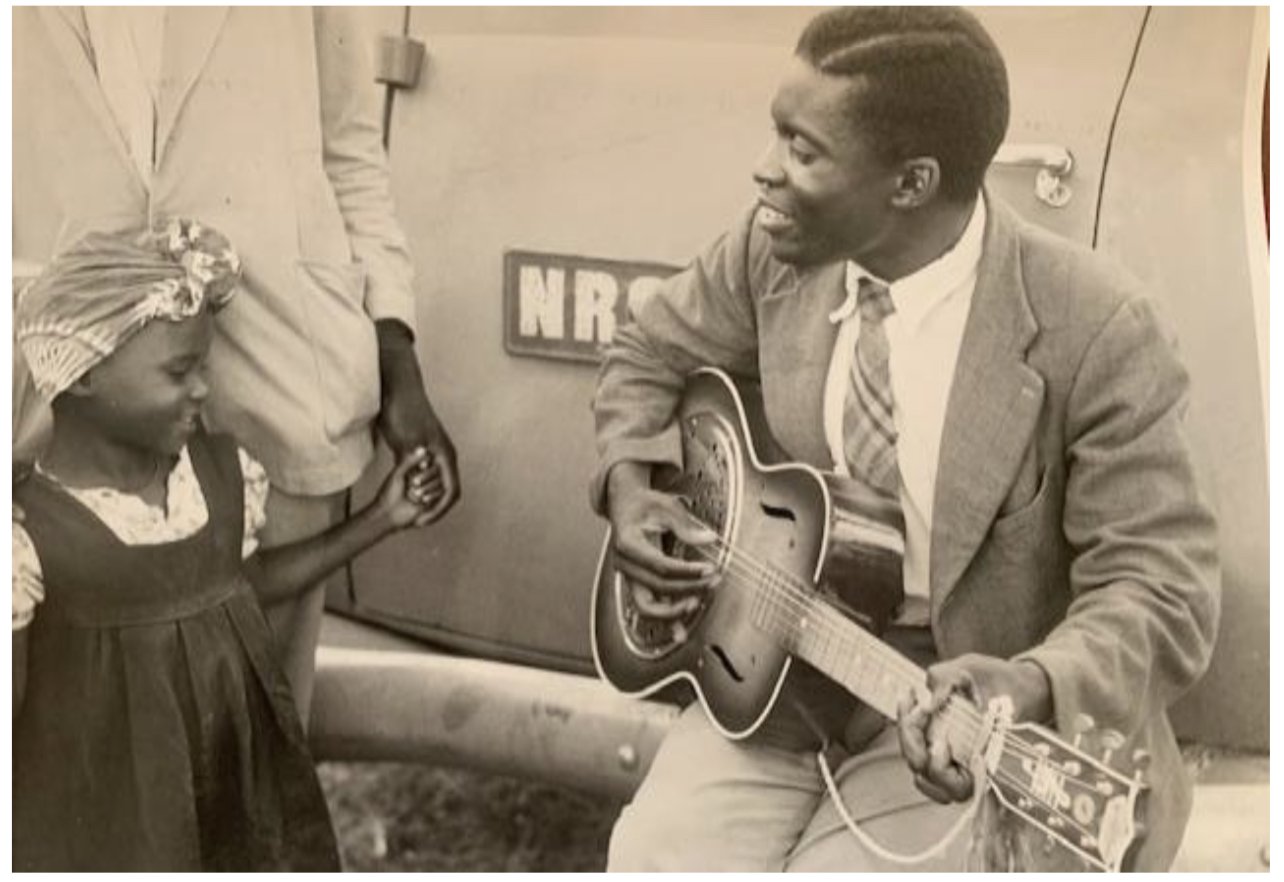

“When I was younger I was really interested in music. Even before I knew I loved art. But my parents were very religious. I would see musicians singing and wished I could do that. So I chose art as something I could do while keeping close to my religion.”

While being denied the opportunity to pursue one’s first choice would have dampened many people’s spirit, Caleb used it as a chance to explore other avenues. And with his abundant talent he still had options in front of him.

“Although it used to kill me inside I had to respect my beliefs. But I had to think what else I could do.

So I started art. I still sing though. But my music is now just for fun. More like a hobby. Sometimes, when I’m not painting, I go to the studio and record. I’ve even done some songs with some of these Zambian artists. But I keep the music to myself.”

While his music was kept to himself, Caleb always shared his art. Sometimes even when he shouldn’t have been.

“I used to do cartoons for nursery schools. I would draw something, take it to them and they would give me some work. I started this in grade eight. So many times I would dodge school to go and draw.

“I never dodged class to go and play or watch movies, because the family I came from was not very well to do.”

The years of lean had an impact on Caleb. Today this day his outlook on life and his work ethic are shaped by those days.

“There was a time I was supposed to pay my school fees and my dad couldn’t pay for me. and that really affected me, cause even if I was in class I was just thinking how am I going to buy shoes, uniform and fees. So when I would sneak from school it was to go to work.

“When you grow up in a not well to do family and you have other friends from well to do families. Their parents are buying them nice clothes, and toys and the like. You also want those things but your parents can’t get them for you. So what do you do? You create. Do that and you start enjoying. Especially when your friends admire and like more than what their parents bought for them. At that time I didn’t know that was art.

“Even when my class mates found out they would tease me. When I would leave they would say things like, ‘mwaya kunchito?’ (you’ve gone to work?). If the teacher would come and find I’m not in class they would say, ‘he has gone for work.’”

Despite the jesting of his school mates, it was at school that his love affair with art truly began. Though he had always been smitten, the influence of a key figure sowed the seeds that would turn his romance to a lasting commitment.

“I was introduced to art by a lady, Mrs Sungela. She was the wife to our headmaster at Kansenshi High School. She believed in my art and I did a project with her. She even introduced me to Visual Arts Council and even paid my membership. She was always pushing me. She was my mother in art. Despite my own mother believing in me, she always believed in me more. So I will always give credit to her.”

As well as Mrs Sungela, Caleb credits fellow artist such as Nsofwa Bowa, Stary Mwaba, and the late Lutanda Mwamba, whose workspace at Visual Arts Council he has taken over.

After completing high school Caleb went onto to work from the Visual Arts Council Ndola office until it was closed. This left him with no option but to move to Lusaka where Visual Arts Council still maintained operations.

“As an artist I couldn’t survive without that place. So that’s why I decided to move to Lusaka in 2006. And here I met old artists from Ndola, like Nsofwa Bowa and others.

“So I started working from here. I started working from the academy in 2007.”

For many people the opportunity to indulge in what they love only really comes in their spare time. After the inconvenience of having to put food on the table, passion is allowed to take centre stage. For Caleb the knowledge that he wanted to pursue art has been within for as long as he can remember. Yet the step taken to establish art as his career path was not taken lightly.

“When I was staying with my uncle in Chelstone, I wasn’t working by then. When I first came to Lusaka I wasn’t making money, it was more like I was still learning. So even when I would come to the likes of Nsofwa I wasn’t making anything. And for my uncle and auntie it was like I was just sitting at home not doing anything. And you know how it feels to be kept. So I was forced to find a job. I even started working. They were happy because I would be paid and I wasn’t just sitting at home.

“But that job didn’t give me time to create. Saturdays I used to work. Sunday I would do laundry and go to church. So I didn’t even have time to sketch.

“And I didn’t even like my job, I was just doing it for the money. All I saw was my career dying.

“And realised I just had to sacrifice. So I told my boss I had to pursue my art. But I didn’t even tell my uncle. It was the hardest part of my life.”

Despite his inability to open up to his uncle Caleb appreciates the part he played in his life.

“He was a good man. And he just wanted what was best for me. I just didn’t know how to tell him

“So I started coming here [to Visual Arts Council] everyday, not even knowing if I would sell any art.”

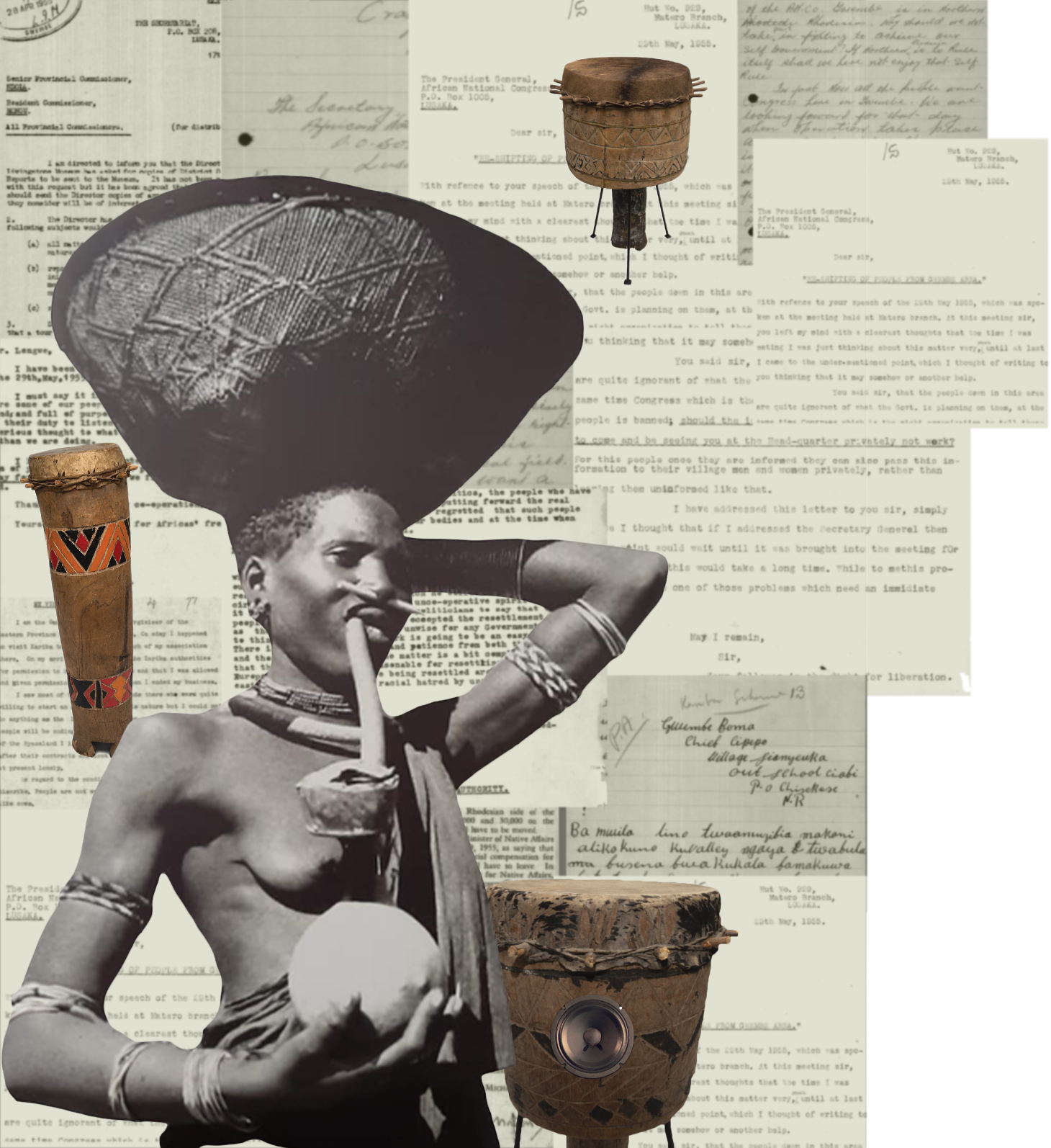

In the ten years since he made that decision Caleb’s career has taken off. Already established as a foremost practitioner in the visual arts circles, Caleb’s surrealist paintings give a glimpse into his understanding of the world in general, but art in particular.

“For me art is to be part of something great. I know that God is the greatest Artist, so I feel He has given us part of His talent to be in this creative world. So I feel special that I have part of my Father’s talent as a Creator.

“It even makes you think wider. Whatever I see now I look at it as an art piece.”

Caleb has travelled extensively, exhibiting his work all over the globe.

“I have travelled across the world. And when I was young I never even saw myself getting on a plane.

“My first solo show was in 2012 in Denmark. Before that I had only participated in group exhibitions.

“It was great. People loved my work. Especially that I didn’t work on the Zambian style life. For many of them it was interesting to see because some had never even been to Africa.”

Despite the broad context of his career, Caleb maintains a very patriotic inspiration for his surreal artwork. In all the work he creates he tries to depict a touch of Zambia and Africa.

“Unless I am commissioned by someone, I only paint about my country and people. I can’t paint about others. I don’t know their lives. I can only paint what I know. And this is what I know.”

Caleb has also known a measure of success in his career so far. He has won a number of awards both locally and internationally. Among these are the 2010 Ngoma award for best upcoming artist.

“That [the Ngoma award] was one of the biggest highlights for me. My people were so proud of me.”

Though nothing makes Caleb prouder than to talk of his daughter, Katongo Esther Chisha. “My daughter is my inspiration. She is named after my mother, who is Katongo. And her mother is Esther.”

Caleb is currently working on his third solo show, the first since 2014. The show, entitled Amalegeni will take a look at hunting birds and other parts of social culture. This is part of Caleb’s view that his works form part of living history.

“What I paint now is something that I’m not seeing now. Kids are not playing like how we used to play. They are just on WhatsApp, Facebooking, on the computers, but for us we used to go swim in the dams, play football, make wires cars…and hunt na ma legeni [with homemade catapults] Talent was there. But now talent is dying because kids just rely on computers.

So I will just be painting on those things that have been forgotten. Such that even 20 years from now, or 100 years if I’m gone, people will be able to say this is where we came from. Because we can see things are changing very fast. I don’t just want to paint a picture that looks beautiful, I want to tell a story.”

And Caleb’s story is one that continues to be told on canvas. The story of a gifted man who creates.

Caleb’s show will take place at Visual Arts Council at Showgrounds in Lusaka on 6th July